Over the last couple of posts we have explored how Tolkien developed the earliest version of a pronominal system for his early Qenya and Gnomish languages by inventing a series of prefixes that could be appended or attached to a verb (ha-tule - it comes) or stand as a separate emphatic form (nimo tanks).

Tolkien codified this system in his Early Qenya Grammar which he composed while he was teaching at The University of Leeds in the 1920’s.

Now let’s explore some examples of how this system of pronouns works in the Elvish Tolkien composed in the 1920’s and 1930’s.

Oilima Markirya - The Last Ship/Ark (c. 1931)

When Tolkien gave his Secret Vice talk on that art of language invention to the Samuel Johnson Society of Pembroke College Oxford on 29 November 1931, he included a series of Elvish poems - three composed in the Qenya language and one in the newly reformed version of Gnomish now called Noldorin.

Twelve extant versions of the first poem ‘Oilima Markirya’ exist - many of which were published in Parma Eldalamberon 16 (Early Elvish Poetry and Pre-Feanorian Alphabets). The versions demonstrate Tolkien experimenting with his language invention and also the meter of the poem. In some versions he tried to reflect the meter of the Finnish Kalevala.

In some versions Tolkien decided to start the poem with the interrogative pronoun ‘who?’ - possibly reflecting the ‘ubi sunt’ of Old English poetry - as in The Wanderer which starts with an interrogative pronoun - Where is the Horse and The Rider?

Hwǣr cwōm mearg? Hwǣr cwōm mago?Hwǣr cwōm māþþumgyfa?

Hwǣr cwōm symbla gesetu?Hwǣr sindon seledrēamas?

Where have the horses gone? where are the riders? where is the giver of gold?

Where are the seats of the feast? where are the joys of the hall?

In the first version that shows evidence of Tolkien’s use of an interrogative pronoun he invents a new word ‘maano’ which does not appear in The Early Qenya Grammar.

Maano kiluvando ninkve Who shall see a white ship

According to the notes there are some false starts listed for this word - mano, man, máno) (PE 16, p. 78)

There is also a line that has the interrogative pronoun ‘what’

ma kaire laikven ondolissen What maimed ships lies upon the green rocks

In the version Tolkien actually read in his Secret Vice talk, each stanza now starts with the revised pronominal form man signifying ‘who’ to create this haunting rhythm.

Man kiluva kirya ninqe Who shall see a white ship?

Man tiruva kirya ninqe Who shall heed a white ship?

Man tenuva súru laustane Who shall hear the winds roaring?

Man kiluva lómi sangane Who shall see the clouds gather?

Man tiruva rusta kirya Who shall heed a broken ship?

In the last line Tolkien varies the placement of the who

Hui oilima man kiluva, hui oilimaite - who shall see the last evening (Secret Vice, pp. 27-29)

Nieninqe

Evidence of Tolkien’s use of the relative pronoun is seen in his fairy themed poem Nieninqe which like Oilima Markirya Tolkien composed several versions of starting in 1921.

In the first version of the poem Tolkien uses the relative pronoun /yan/

Elle tande Nielikkilis Thither came little Nielikki

tanya wende nieinnqea that maiden like a snow drop

yan i vilyar anta miqilis whom the air gives gentle kisses

Under this version Tolkien wrote this revealing statement

‘This language I may say (though it remains [? perhaps] incomplete - and has often endured grammatical changes especially with verbs) was written of course to the needs of my mythology. I found it necessary to have at least some clear idea of the language spoken by my fairy creatures (the Eldalie) in order to understand them - and of course to invent their names. So that they should be different & yet the same.’ (PE 16, 92)

In the version Tolkien gave in his Secret Vice talk - /yan/ is changed to /yar/ thus introducing an alternative conception of the relative-clause syntax with the relative pronoun now inflected to indicate its role in the relative clause - with yar now meaning ‘to whom’

yar I vilya anta miqilis - to whom the air gives kisses (SV, p. 30)

However, in a later version of the poem from the 1950’s Tolkien reverts to using /yan/ which brings it in line with the Quenya from The Lord of the Rings period (more to come here!)

The Father Christmas Letters and Arctic Language

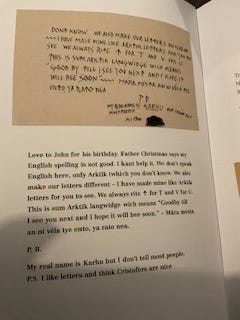

Let’s end this post with an interesting line of Qenya that comes from one of the letters that Tolkien wrote in the role of Father Christmas to his children each year. In November 1929 a letter arrived for the Tolkien children from the North Pole. The composer was one of Father Christmas helpers Karhu the Polar Bear. At the end of the letter Karhu writes:

Love to John for his birthday, Father Christmas says my English spelling is not good. I kant help it We don’t speak English here, only Arktik (which you don’t know)……This is sum Arktik language wich means ‘Goodby till I see you next and I hope it will bee soon' - Mara mesta an ni vela tye ento, ya rato nea.’ (Father Christmas Letters, p. 58).

The farewell from Karhu may be known as Arktik but it is clearly Qenya and it has several Qenya pronouns in it and the pronouns are separate emphatic forms:

ni vela tye - I see you

In the next post we will look at some more early examples of pronouns in Qenya and also Noldorin sentences from the 1920-1930’s.

Namárië for now!